We have been encouraged to shift about and ride with all of the guides, as each has different perspectives, stories, and expertise. Still, Clark needed to simplify things this morning and so re-joined Christian in the sweep boat. And it happens that Eliza and Todd also jumped back on the same boat as yesterday. Smart move for them, as I was OK with staying in the back all day to deal with my sand-in-eye issue, so they got a full day up front. This will set a new pattern for our partners in the Fab Five, as, with the possible exception of Lana, we’re all keen to ride up front as much as possible. So our couples will be endeavoring to not ride too much as a foursome, as each pair wants the same seats as the other!

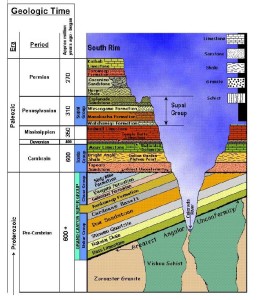

Today, plunging deeper into the canyon forces us to expand our minds in the geological direction as well. As the day began, we felt ourselves all knowledgeable, having mastered the notion of a “formation”, that is, a group of rocks that is readily distinguishable from layers above and below. Our first formation was the Kaibab Limestone so naturally we thought a “formation” meant a layer of one type of rock. But then we had to come to terms with the Toroweap layer, sandwiched between the Kaibab Limestone and the Coconino Sandstone. But that middle layer has three main types of rocks—and no one is calling it the “Toroweap Gypsum and Shale and Sandstone”, it’s just the “Toroweap Formation”.

The point is a formation has a recognizable structure that geologists use to build their maps and that even we non-geologists can spot as a distinct layer. Its main observable characteristic is it seems more bust-up-able, so the Toroweap also introduced us to talus slopes. Turns out the gypsum and shale are more susceptible to erosion, so the transition between Kaibab and Coconino is a sloping mess of tumbled and jumbled rock, providing footholds for vegetation and for wildlife. The Hermit Shale, underneath the Coconino, also turns out to be a slope-forming layer. So we are sometimes going past vertical walls but sometimes alongside rocky slopes hosting vegetation—and wildlife.

One Big Rock Slide–from the Kaibab over the Toroweap talus slope to drop off the Coconino wall to the Hermit shale slope

Well, we thought we were so smart, but our comeuppance struck earlier this morning, when we descended below the Hermit Shale into something entirely new. The Supai Group. What the heck is a “group”??? Is this some kind of pun on “rock group”? Are we supposed to be asking which layer plays “bass”? Naw, it’s just that sometimes geologists find it helpful to describe an assemblage of formations as a “Group”. There are four formations (is that another pun?) in the Supai—and we will have rolled through all of them by dinnertime. Why “Supai”? That’s the name of the people who live in the Grand Canyon, the members of the Havasupai Tribe. Not coincidentally, “Coconino” is the old Hopi name for the Havasupai. So far, the geologists seem to have been relying on the locals to come up with formation names—Kaibab and Toroweap are Southern Paiute words, which are usually translated as “mountain lying down” and “dry/barren valley”, respectively. We’ll learn about the “Hermit” moniker later.

With all these complex rocks in the vicinity, after lunch we make a short run to a place for a hike. We pull in at Upper North Canyon Camp…no, not to camp, instead to make the scramble up to the North Canyon pool. It’s a try-out, Billie says, to see how the group fares on hikes involving some scrambling. I’m having something of a relapse in my eye condition, so I (yeah, yeah, grumpily) stay behind to take care of that. I like scrambling, but it’s not a good idea when you can’t see. Meanwhile, Christian is also on break, left behind to keep an eye on the boats and any stay-behind passengers. I think I’m the only one staying. Oh, well.

When my eye is feeling better again, I let Christian know I’m going to roam about in the area near shore, with my camera in hand. It’s actually a relief to have a little time seemingly “on my own”. (This has to go in quotes…there are tons of people around, no fewer than a dozen at any given time, as other groups leave and arrive from the river, or from up-canyon.) I just ignore everyone else and find for myself some photogenic calcite lumps, fire ants, lizards, a garden of native plants (agave, prickly pear, and more), and a spot to video the rapids.

It is an effort to ignore just how popular this spot is. I’ve already learned to be careful setting up a shot when folks are first pulling in to shore. The very first thing guys do after shipping oars—whether they’re wriggling out of a kayak or beaching a raft– is stand up and urinate. Another reason to roam a bit away from the beach.

While I may have enjoyed my little wander and my personal discoveries, I did miss the adventure of the day, so here are a few of Clark’s pics from the Reason So Many People Stop Here:

It’s not far to camp, but it’s a fun ride. We’re now in the “Roaring Twenties”, a sequence of lively rapids between the 20-mile and 30-mile rivermarks. At camp, another benefactor appears. Trillian (of the triad Art & Trillian & Barry) has a solid familiarity with the trials of irritated eyes, as she suffers with one of those ailments that interferes with tear production, so she shares a pair of vials of her prescription Restasis. I was a little skeptical about “borrowing” a prescription medication, but it turns out to be just the right thing.

Another lovely freshly-prepared dinner. This time, it’s grilled chicken—with a choice of sauces. Clark is ecstatic. I think he goes back for seconds. Matt works out his golf technique with the help of some driftwood. Like Clark, he’s looking forward to the Master’s this coming weekend; unlike Clark, he will be at home in time to watch the whole tournament.

During dessert, the portable grill becomes a firepit for our circle of chairs.  The crew breaks out some toys—horseshoes and a set of glow-in-the dark bocce balls. Everyone is in the mood for some relaxation. I’m in the mood for taking more pictures.

The crew breaks out some toys—horseshoes and a set of glow-in-the dark bocce balls. Everyone is in the mood for some relaxation. I’m in the mood for taking more pictures.

We made over close to 20 miles today (even with that annoying person whining in the back of the sweep boat). We’re having wonderful weather. A little drizzle during the hike just added a little variety without causing any problems for anybody. We’ve stopped at Lone Cedar Camp, which is big enough for folks to spread out a bit. Our tent is tucked into the lee of a large rock, and I persuade Clark to try putting up the flysheet tonight (the excuse being it might rain again). The combined effect is to reduce somehat the quantity of sand infiltrating our tent this time.

Wishing I owned a sleep mask—or that I’d happened to pack one of my several headbands—I fashion an eye covering from a spare pair of long johns (well, let’s say “elegant thermal underlayer”) which serves to keep my head warm in the night and to keep the Restasis (and the extra tears it produces) in and to keep the sand out of my eyes. At least no one at all can see how silly I look—Clark is already fast asleep.